‘This is one of the worst days in Irish history!’

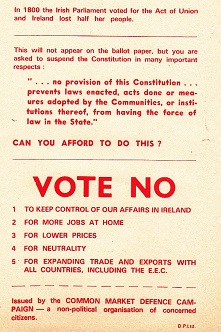

I remember the first day of January, 1973 as though it were last Monday. I was 17, studying (or, mostly, not) for my Leaving Cert, which I was to sit the following June. Over the Christmas holidays, as was my practice, I travelled with my father on his ‘stagecoach’ runs, helping with the mailbags and newspapers, emptying the pillar boxes, acting as door-opener for passengers, and generally riding shotgun. Normally, the mailcar was a clamour of argument, disagreement, insults, laughter and the occasional shouted ‘Yahoo!’ This day it was different — funereal, mainly in deference to my father’s mood, which was uncharacteristically morose. ‘This’, I heard him say to passenger after passenger, ‘is one of the worst days in Irish history!’ The decision to join the ‘European Common Market’, voted on by the Irish people the previous May, and carried by a landslide of 83 per cent to 17, with a turnout of 70 per cent, came into effect that day. My father, who had been one of 211,891 Irish people to vote against joining, believed membership would lead to the destruction of the Irish farming and fishing industries, and make us the paupers of Europe. He insisted that the required trade-offs — especially the exchange of sovereignty and natural resources for infrastructure and subsidies — would erode our longterm capacity for self-sufficiency, bringing with it renewed dependency, deceptively easy money, increasing debt and a degeneration of our political class. He was right on every score. If he were alive today, he would take no pleasure in his ‘vindication’, even though the evidence is to be seen all around.

This perspective was as though in my blood, and I articulated it for many years, encountering a high degree of abuse and ridicule along the way. The argument against Ireland’s membership was especially unpopular during the 1980s and early 1990s, when large amounts of structural and cohesion funding became available and Ireland was a net beneficiary of community largesse.

In 1972 and even in the years after we joined, we had hopes of developing an indigenous self-sufficiency, while using our membership of the European Community in ways that might eventually have supported an independent nation and culture. On paper, the Irish population should be capable of sustaining itself without difficulty on what is available to it. But nobody in Irish politics at the time was offering a coherent vision concerning how this might be pursued. Whenever Irish objectives were at odds with the drift of the community, we chose to accept monetary compensation rather than insisting on retaining certain essential capacities and resources within our control.

For most of the century since achieving nominal independence from England, Ireland had struggled to survive and to maintain its population. In the 1930s, and again in the 1950s, we suffered enormous haemorrhaging of our people, a pattern that had persisted since the Great Famines of the 1840s. There was a brief respite in the 1970s, arising from a momentary optimism created by a new kind of leadership — leading people to imagine that we had made a wise move in joining what was then the EEC — but emigration resumed again in the 1980s and persisted until the ‘miraculous’ boom of the 1990s.

Today, Irish agriculture comprises mainly beef and dairy farming, by far the least efficient use of land. If you drive around the fabled countryside of Ireland, you cannot avoid noticing that almost none of the land is cultivated, and this is a symbol also of other oversights and neglects. Our fisheries are mainly exploited by Spanish fishermen because this was part of the firesale that enabled us to construct the vestige of a ‘modern’ society we have now. Our tourism industry is in the doldrums because we cannot decide which version of ourselves — traditionalist kitsch, or cutting-edge modernity, or tax haven — we wish to promote.

The two brief periods of resurgence of the Irish economy in the 1970s and 1990s were based mainly on two phenomena — budget deficiting (i.e. borrowing) and invited dependency. Today, we are per capita one of the most indebted nations in the world. The economic model pursued by latter-day politicians has been one which abandoned development of indigenous resources in favour of doing deals with the outside world. Ireland gave itself the lowest corporation tax rate in the world, so as to attract multinational operators with a view to attracting employment, thus obviating the necessity for deeper thinking. Our fishing rights were traded as part of our European Union membership, in return for structural funds to build motorways. Nobody in our political class today offers any vision by which Ireland might proceed outside the EU or in a reduced role within it. Our leaders know no other way of running our country except in some kind of dependent relationship with some larger entity.

It is a cliché of Irish politics that ‘we are all Europeans now’, but any close observer of the discussion since it began would have to conclude that nobody had any real interest in anything except the structural and cohesion funding. The founders of the 'European project’ — Monnet, De Gasperi, Adenauer, Schuman — are almost unheard of in Ireland. Very few Irish people would be able to mount a convincing argument concerning the cultural and spiritual characteristics of Ireland’s place in that ‘project’. Unsurprisingly, given that the project was sold for three decades as an opportunity to obtain financial hand-outs, voters remained cynical about any attempts at describing a deeper connection.

I was for many years deeply suspicious of the European project, mainly because of its bureaucratic dimension and the way it treated democratic endorsement by way of a rubber-stamp on decisions already taken by politicians and officials. I had strenuously opposed the Maastricht Treaty in the referendum of 1992, which was really the moment of no-return for Ireland as a going concern on its own steam, at least under the guidance of the kinds of politicians we had started to throw up. With that treaty, the EU ceased to be merely a cooperative community, acquiring many of the characteristics of a single political entity. I had assumed that, in voting Yes to Maastricht, the Irish electorate was aware of the choice it was making. It seemed obvious that the argument for an independent, self-sufficient Ireland was lost. Ireland had become so dependent on the relationship with the community that, henceforth, almost everything that concerned our future would have to be pursued from an acceptance of this dependence. I remember well the condescension and hostility of the political and media establishments back then, as we sought to persuade people that voting Yes to Maastricht would be the most disastrous decision we would ever make. Later, I argued against European Monetary Union and the introduction of the Euro, but was on the losing side of these arguments also. These developments resulted in the Celtic Tiger, a materialist carnival that lasted for ten years, and which the Irish people in general embraced as though it were the arrival of the Promised Land, the outright vindication of the choices they had made. I politely continued to point out that this was delusional, that the prosperity we were enjoying lacked a solid basis. But, in the face of what appeared to be the facts, I eventually stopped talking. Today, it gives me no great pleasure to say that everything I heard my father warn about has now come to pass.

For nearly 50 years, the very idea of Ireland as a nation-state has been subjected to the cultural equivalent of carpet bombing — every hour of every day, from every newspapers and broadcasting station. The Irish people have been subjected to relentless propaganda concerning the merits, the inevitability and singular correctness of the EU project, and of the invalidity and indeed moral questionableness of the national idea. This has penetrated into every remaining crevice of public thinking, although these are now few and far between. At the time of the Maastricht referendum, I used to ask people why it was that the unity and self-realisation of a larger entity like the European Union was to be regarded as ipso facto good, whereas the self-realisation of a smaller entity, like Ireland, was to be regarded as dangerous and wrong. Nobody could coherently answer this question except with the old justifications for European integration: to prevent a recurrence of the world wars of the 20th century. So, the reason we acquiesced in the beggaring of our children’s children is to discourage the Germans from reducing Europe to rubble for a third time. . .

Europe is a continent rich in culture and history, the centre of the Christian civilisation that transformed the world. The EU is a bureaucracy, which treats culture as something irrelevant and non-essential, soul as some residual anachronism, and faith as something to be 'tolerated' rather than embraced. In the absence of a cultural and spiritual vision, the economy has become at once everything and, inevitably, a nothing.

This failure of the EU project to capture the imaginations of its people is not merely 'coincidental' with the retreat from Europe's rich Christian heritage. There is a causal relationship between the two. The retreat from an understanding of first causes — once loudly and proudly expressed in the Christian narrative and transmitted via the richest culture the world has known — has left a vacuum which economics, liberalism and materialism has unsurprisingly failed to fill.

For various reasons, what evolved into the EU was never articulate about itself in cultural terms, but instead resorted to a language and logic of materialism and secular democracy. Its drivers made the mistake of thinking that a society can form itself willy nilly out of a melting pot of ethnicities and cultures. Instead, what happens in such experiments is that, without a strong and assertive host culture at the centre, the multicultural mishmash lacks any context for unity, and so divides into a multiplicity of enclave entities. This process can be seen in many European countries — in Holland, France, Sweden, the UK, where immigrant populations, attracted by prosperity and modernity, converge for economic reasons only, and end up weakening rather than strengthening the host cultures they seek to live off. In the same way, all of the member countries of the EU are as immigrants to the idea of European Union. They came to it in hope and expectation, but having got there have found the core vacated, a hole in the doughnut of the unity they anticipated. Thus, fundamentally, the EU and Europe have no prospect of ever being coterminous entities.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Source: John Waters Unchained. IMG: irishelectionliterature.com

AWIP: http://www.a-w-i-p.com/index.php/2023/01/07/lemgthis-is-one-of-the-worst-days-in-irish-history-l-emg