The Trembling Voices of Those Terrorized by America’s Drone Campaign

David Harris-Gershon

Families cannot sleep together for fear of appearing, in the eyes of a drone, as a dangerous gathering. Village elders cannot meet according to tradition to discuss resource allocations because, in the eyes of a drone, they may be deemed a nefarious group. Citizens cannot gather to plan a nonviolent protest against drone attacks for fear of being killed by them.

The voices you are about to hear belong to individuals the United States may soon kill or maim – whether with clear-eyed intention as pinpoint targets or by mistake.

They belong to those who have – for years – been terrorized by our country, those who continue to be terrorized by our country, those who are bereaved and fearful and paralyzed because of our country.

They are voices belonging to drone attack survivors from the village of Datta Khel in the Pakistani region of North Waziristan, voices collected by the U.K. human rights group Reprieve and included in a lawsuit filed against the British government for aiding America’s unaccountable and illegal drone campaign.

They are silent, trembling voices – voices we don’t hear often (if at all). Voices I recently encountered thanks to Harper’s. Listen:

The first time I saw a drone in the sky was about eight years ago, when I was thirteen. I have counted six or seven drone strikes in my village since the beginning of 2012. There were sixty or seventy primary schools in and around my village, but only a few remain today. Few children attend school because they fear for their lives walking to and from their homes. I am mostly illiterate. I stopped going to school because we were all very afraid that we would be killed. I am twenty-one years old. My time has passed. I cannot learn how to read or write so that I can better my life. But I very much wish my children to grow up without these killer drones hovering above, so that they may get the education and life I was denied.

¤ ¤ ¤

The men who died in this strike were our leaders; the ones we turned to for all forms of support. We always knew that drone strikes were wrong, that they encroached on Pakistan’s sovereign territory. We knew that innocent civilians had been killed. However, we did not realize how callous and cruel it could be. The community is now plagued with fear. The tribal elders are afraid to gather together in jirgas, as had been our custom for more than a century. The mothers and wives plead with the men not to congregate together. They do not want to lose any more of their husbands, sons, brothers, and nephews. People in the same family now sleep apart because they do not want their togetherness to be viewed suspiciously through the eye of the drone. They do not want to become the next target.

¤ ¤ ¤

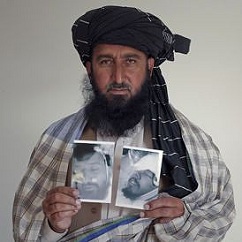

I am approximately forty-six years old, though I do not know the exact date of my birth. I am a malice of my tribe, meaning that I am a man of responsibility among my people. One of my brother’s sons, Din Mohammed, whom I was very fond of, was killed by a drone missile on March 17, 2011. He was one of about forty people who died in this strike. Din Mohammed was twenty-five years old when he died. These men were gathered together for a jirga, a gathering of tribal elders to solve disputes. This particular jirga was to solve a disagreement over chromite, a mineral mined in Waziristan. My nephew was attending the jirga because he was involved in the transport and sale of this mineral. My brother, Din Mohammed’s father, arrived at the scene of the strike shortly following the attack. He saw death all around him, and then he found his own son. My brother had to bring his son back home in pieces. That was all that remained of Din Mohammed.

¤ ¤ ¤

I saw my father about three hours before the drone strike killed him. News of the strike didn’t reach me until later, and I arrived at the location in the evening. When I got off the bus near the bazaar, I immediately saw flames in and around the station. The fires burned for two days straight. I went to where the jirga had been held. There were still people lying around injured. The tribal elders who had been killed could not be identified because there were body parts strewn about. The smell was awful. I just collected the pieces of flesh that I believed belonged to my father and placed them in a small coffin.The sudden loss of so many elders and leaders in my community has had a tremendous impact. Everyone is now afraid to gather together to hold jirgas and solve our problems. Even if we want to come together to protest the illegal drone strikes, we fear that meeting to discuss how to peacefully protest will put us at risk of being killed by drones.

There are many destructive, distressing sides to the drone campaign waged by the Obama administration in Pakistan and Afghanistan.For one, from a national security perspective – our own national security, that is – it’s patently clear that the civilian suffering and rage brought on by errant drone attacks are creating enemies who would like to stand against us.

Peter Oborne wrote recently in The Telegraph what we all know (or should know):

In the US, drone strikes are a good thing. In Pakistan, from where I write this, it is impossible to overestimate the anger and distress they cause. Almost all Pakistanis feel that they are personally under attack, and that America tramples on their precarious national sovereignty.[...]

Supporters of drones – and they make up practically the entire respectable political establishment in Britain and the US – argue that they are indispensable in the fight against al-Qaeda. But plenty of very experienced voices have expressed profound qualms. The former army officer David Kilcullen, one of the architects of the 2007 Iraqi surge, has warned that drone attacks create more extremists than they eliminate. Sir Sherard Cowper-Coles, Britain’s former special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan, is equally adamant that drone attacks are horribly counter-productive because of the hatred they have started to generate: according to a recent poll, more than two thirds of Pakistanis regard the United States as an enemy.

Then, there’s the distressing amount of power – too much, many argue – that our President now has in executing what are essentially miniature acts of warfare, repeated incessantly over a region we can’t see and don’t often hear about using unmanned aircraft.As The New York Times broke this week, Obama “has placed himself at the helm of a top secret ‘nominations’ process to designate terrorists for kill or capture,” pledging (absurdly) to do so in a way that aligns with “American values.”

Nevermind that it’s impossible, so far as I can tell, to align the killing of American citizens without a trial or due process with American values. It’s likely impossible to align it with the law.

In the end, though, what remains – what is real – are the voices in Pakistan. The suffering. The traumas. The confused and dazzling rage.

Families cannot sleep together for fear of appearing, in the eyes of a drone, as a dangerous gathering. Village elders cannot meet according to tradition to discuss resource allocations because, in the eyes of a drone, they may be deemed a nefarious group. Citizens cannot gather to plan a nonviolent protest against drone attacks for fear of being killed by them.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Article published here: Tikkun Daily

URL: http://www.a-w-i-p.com/index.php/2012/06/02/the-trembling-voices-of-those-terrorized