BALKAN DONBASS

Объясняет Readovka

Lessons from the Serbian Krajina for Russia

Everything in history has happened before. The problem of Russia and the Russian republics of Donbass is not unique, and the nearest analogue we find is not at all far away. The Serbian Krajina is a republic that is not on the map these days. It was destroyed by the Croatian armed forces in 1995. However, before Croatia defeated the Serbian insurgency, the Serbs defeated themselves. From the sad history of Krajina we can learn something important for ourselves: the leaders of the Serbian republic and "big" Yugoslavia, bogged down in negotiations, contractual arrangements and corruption schemes, were powerless to confront the challenge that had confronted them.

A house divided – The lands along the south-eastern borders of present-day Croatia long served as the border between the Ottoman Empire and Austria. Serbs who fled from under the Sultan's heavy hand acquired a status similar to the Cossacks in Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth - they enjoyed rights and privileges in exchange for military service and protection of their new homeland from the Turks.

However, in the nineteenth century, when national consciousness began to grow across Europe and the Austrian government demilitarized the border, a rift naturally developed between the Serbs and Croats living in the area. The Croats perceived the Serbs as newcomers (even though they had been living there for centuries), whereas the Serbs were proud of their own history of living in the area.

World War II left scars that were simply impossible to eradicate. What was done to the Serbs who lived in Croatia could be boldly qualified as genocide. The Croatian nationalist movement of the Ustashas carried out a massacre in which hundreds of thousands of people were killed.

Within post-war Yugoslavia, inter-ethnic tensions were contained by the deliberate efforts of the Tito regime. After Tito died, however, his state quickly began to disintegrate. National problems escalated in the late 1980s. As was often the case, it began with rallies over questions of language and cultural rights. However, the Croatian government refused to compromise.

In May 1991, Croatia held a referendum on independence. Even before that, the Serbian population had been subjected to de facto severe discrimination. Franjo Tudjman, the new leader of independent Croatia, and his entourage insisted on severe restrictions on the rights of Serbs to national and cultural autonomy.

Parallel to the Croatian one, however, there was a growing national upsurge already among the Serbs of Croatia. Initially, the Serbs were not rigidly opposed to secession from the new republic. However, the Serbs were mostly compactly settled in a few communities, mostly along the border with neighbouring Bosnia, and they believed they were entitled to their own national autonomy.

In July 1990, even before Croatia formally seceded from Yugoslavia, Croatian Serbs declared autonomy. The declared demands were mainly related to cultural aspects: schools, the Cyrillic alphabet press etc. A representative body, the Serbian Sabor, was also being set up.

Curiously enough, from the outset Croatian leaders were convinced that the Serbs were acting according to a script that had been dictated to them in Belgrade. As one can easily see from the example of Donbass, the situation when an uprising is mistaken for foreign machinations has been reproduced in a variety of eras.

There are also some familiar motives in the Croatian response to Serb attempts at autonomy. Croatian Serb leader Jovan Rašković proposed a compromise in which Serbs remain loyal to Croatia, but Zagreb's policy towards them remains soft and Croats do not infringe on minority cultural rights. However, from the point of view of Croatian leaders, any attempt by Serbs to speak out about their rights was a manifestation of "vile separatism".

When Serbs tried to hold a referendum on autonomy, Croats used the police to disrupt the event. However, the police faced organised resistance at the barricades.

The capital of the Serbian insurgents - they could already be called that - was the town of Knin, where the Serbian autonomous region Krajina was proclaimed on December 21, 1990. Its name is usually shortened to Serbian Krajina. Interestingly, it still declared itself a territorial autonomy within Croatia, with an important caveat - within the Federal Yugoslavia.

At that time there were two main currents in the Krajina: apart from Rašković, who proposed soft autonomy, Milan Babić, a supporter of a more radical course, came to the fore. Slobodan Milosevic, the Serbian leader who supported Krajina and declared that the separation of his people was unacceptable, held his own. The Serbs in Krajina were of the same opinion. As soon as Croatia announced its secession from Yugoslavia with a special resolution, Krajina declared that it did not recognise the resolution, remained in one state with Serbia and withdrew from Croatia. In effect, this meant war.

The year 1990 was marked by constant illegal arrests and sporadic killings, the vast majority of arrests and killings of Serbs. Croatia went on a "witch hunt" and armed units were formed in Serb enclaves.

War – In 1991 Croatia began fighting. In Yugoslavia, before its collapse, much attention had been paid to the formation of territorial units that would form the basis of guerrilla resistance in the event of an external invasion. However, in fact the arsenals and cadres were used to form national armies. In addition, from the beginning Croatia was tacitly receiving arms from Europe.

In turn, the Serbs could count on the help of the regular forces of the Yugoslav People's Army.

Nationally-motivated criminal assassinations had been going on for a long time, but in the spring of 1991 the full-scale systematic fighting had begun. Serbs and Croats alike were mercilessly massacring the opposing side, including, as if not primarily, civilians. At the same time the world community was faithfully broadcasted at best half of the picture, portraying Serbs as rampaging murderers. Neither the discrimination against Serbs in pre-war Croatia nor their killings during the war were of any interest to the world.

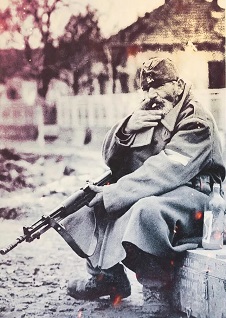

Serbian commanders were mostly charismatic personalities with no special military skills. It was usually a question of rural militia action altogether. The state of affairs in Krajina can be compared with the situation in Donbass in 2014 - the units created on the fly were not distinguished by high discipline.

The area of Serb control ran mostly along Croatia's eastern border, with Knin at its centre. A separate enclave was Eastern Slavonia, an unconnected zone in the far east of Croatia.

The Yugoslav army initially tried to maintain neutrality. The Croats blockaded the UNA garrisons and seized weapons, sometimes with human casualties. At the same time, the UNA leadership stoically ignored the situation in the Serbian Krajina for a long time. It took some time to recover, but they finally attacked in the Knin (central Krajina) and Vukovar (eastern Slavonia) areas.

The apotheosis of the war was the battle for Vukovar. This town, with a population of about 40,000 people, was one of the most ethnically diverse in Yugoslavia. Serbs and Croats lived there almost equally, and a third of the marriages were mixed. In 1991, a series of Serbian pogroms were organized there, effectively expelling and destroying the Serbian community.

The Serbs used regular army units to storm the town. In August 1991, the Serbs blockaded the garrison and after three months of street fighting took the city by a fierce assault. The Serbs acted bravely, but not with much skill, and suffered heavy casualties in the streets from flying squads of Croatian anti-tank units. The battle resembled a miniature version of the battle for Grozny. After unsuccessful initial assaults, the Serbs entered the streets, pounding their way with a hail of artillery shells. In November, the Serbs occupied the ruins of Vukovar at the cost of more than a thousand soldiers and militia. 1,800 died on the Croat side, and about 2,000 civilian casualties. Another 1,500 Croats were taken prisoner.

The battle for Dubrovnik was somewhat less fierce, but just as hard. This city on the Adriatic Sea in the very south of Croatia was besieged by the Serb units in the autumn of 1991. The city was not well suited for defence, as it stood on the coast, fringed by mountains. Having thoroughly cut off the town from the approach of reinforcements, the Serbs broke through on the approaches to the town. Dubrovnik's historic buildings suffered serious damage from the shelling, but it was never taken definitively by the Serbs.

The drama of Vukovar and Dubrovnik raised the stakes. Yugoslavia's international situation had deteriorated sharply, and the press praised the Serbs in every way. The UN Security Council took the initiative to send peacekeepers to Croatia.

Treaty – By November 1991, the Serbs had taken possession of most of the territory where they had hitherto been in the majority. However, the question was what to do next.

The Serbian ruler Slobodan Milosevic played a hugely destructive role at this stage. Back in the spring he met with Franjo Tudjman, his formal opponent, at the Karadjordjevo estate. The exact content of these talks remains unknown, but Belgrade's further steps give the impression of some kind of collusion, which was consistently put into practice. First, in the autumn of 1991, the Yugoslav Army began to withdraw its support to the Krajina Serbs. Thus, on 3 November, Serbian forces surrendered a number of positions in Western Slavonia. Volunteer units were left without support and driven out of there despite desperate resistance. In addition, the operation in the Dubrovnik area, which the Serbs had won without five minutes, was effectively halted. Milosevic felt that it was now necessary to consolidate what had been achieved on the battlefield. As counter-intuitive as it may sound, it was he who invited the international peacekeeping force to Croatia. Belgrade requested a peacekeeping force from the UN between Serb and Croat forces. On 23 November 1991, in Geneva, Milosevic and Tudjman signed an agreement on a ceasefire and the deployment of peacekeepers in Croatia.

Yugoslavia undertook to withdraw its own troops from Croatian territory, and only local militias remained in the self-proclaimed republic.

The security of Croatia's Serbs was transferred to an international peacekeeping contingent. From that point on, the Serbs were doomed.

"It is for this reason that I have always opposed the introduction of foreign peacekeepers into the Donbass," noted historian and Balkan specialist Mikhail Polikarpov on this occasion. - "It is important to understand that these peacekeepers cannot be neutral.

It is interesting, by the way, that Croatia insisted on the deployment of peacekeepers exactly on the border with Bosnia and Serbia. This way it was supposed to cut off the militias from assistance.

Meanwhile, in Knin they proclaimed a Republic of Serbian Krajina. Milan Babić, who became its first president, was trying to find a way out that would allow the Serbs to maintain their independence. Babić believed that UN peacekeepers would simply cover the defeat of Serbian Krajina the moment Croatia felt strong enough to do so. Milosevic, for his part, demanded compliance with the decision of the international institutions and denied Babić the "radical", although the "radical", as seen after the fact, simply put two and two together and described precisely the scenario that was put into practice.

Milosevic, through some ingenious scheming, ousted Babić in favour of the more moderate Goran Hadžić. Within the Krajina there was a turmoil that culminated in the push for a moderate line.

UN peacekeepers gave the Serbian Krajina three years of relative calm. From 1992 to 1995 the republic lived a relatively normal life. The Serbs were trying to rehabilitate the economy, and even to organize some sort of economic reintegration with Croatia. At the same time, projects for a political solution to the crisis were being prepared. In the mildest version of reintegration, only Knin, one of the three provinces of the Serbian Krajina, would receive autonomy. The Serbs were willing to accept this option, although it left them with few of the gains of 1991.

However, Croatia did not accept this settlement either. It was quietly preparing for a blow that would have turned the tide of the conflict in its favour at once. Along the way, Croatia was engaged in a war over the fragments of Bosnia, where Tudjman eventually joined forces with the Bosnian Serb "Muslims" against the Bosnian Serbs.

Meanwhile, Croatia was building up the army's fighting capabilities. The republic's armed forces were reforming and rearming. Western countries supplied weapons to Croatia, despite the formally applicable embargo. In addition, MPRI provided training of combat units, intelligence and planning assistance to the Croatian officers. With the talk of peace the Croats have created a powerful strike force, radically superior to anything that was available to the Serbs.

Serbia, in turn, has done nothing to strengthen Krajina, with the fight against Chetnikism resulting in an exodus of volunteers from Serbia and Montenegro.

The first bells rang in 1993, when Croatia conducted local operations in the Maslenica and Medak areas. In both cases, the Croats inflicted non-critical but painful defeats on the Serbs. Although the peacekeepers and the UN behind them protested against the Croatian actions and exerted political pressure on Zagreb, the Croats drew very definite conclusions from these local battles. First, UN peacekeepers cannot and will not be truly effective in preventing a resumption of hostilities. Secondly, Serbian defences are weak. Thirdly, the UNA will no longer provide active support to the Serbs in Krajina.

In addition, this peace period was accompanied by some more concessions from the Serbs. For example, the highway between different parts of Croatia through Serb-controlled territory was opened. The unblocking of the highway was accompanied by the removal of minefields in this sector.

Armed with new knowledge, Croatian military and political leaders devised an operation that led to the total defeat of the Serb Krajina. By 1995 they had achieved a serious advantage in both numbers and quality of troops. A tenfold numerical advantage, which is often cited, was lacking, but a threefold advantage in men and roughly twice that in major ground combat equipment gave Croatia a comfortable advantage in forces.

The Croatian armed forces' operation was called "Lightning". It lasted literally three days from 1 to 3 May 1995 and resulted in the complete collapse of the Serbian forces in western Slavonia, one of the three insurgent areas. The UN peacekeepers, represented by three battalions (from Jordan, Nepal and Argentina), simply let the Croats through their positions. The Jordanians were neutralised with a minimum of resistance, the Nepalese barely escaped fire. The Serbian population partly fled, partly were deported - some 15,000 Serbs fled the enclave, only 800 remained.

Now it was Knin's turn. The offensive was conducted jointly with the Bosnian Muslim troops - the Serbian Krajina was tightly adjacent to the Bosnian border. The offensive also lasted only a few days. On August 4, the Croats and Bosniaks struck. Basically, they went through the Serb defences like a hot knife through butter. The peacekeepers were detained by the Croats, and where they tried to resist, it was broken: so the Danish roadblock came under attack, killing one of the peacekeepers.

On the third day of the operation, Krajina was cut into pieces, and a unified defence of the Serbian Krajina simply did not exist. At best, Serb units provided evacuation of civilians.

Knin fell on 5 August. On 9 August the Serbian Krajina ceased to exist.

Croats lost fewer than 200 people dead, including 1 brigade commander. The Serbs lost at least 1,800, including at least 1,200 civilians. Up to 300 more Serb civilians were killed by the victors after the fighting ended. A number of settlements were destroyed by the Croats after the capture. Four peacekeepers were killed (three by Croats, one by Serbs). Up to 250 thousand Serbs have escaped the republic. Only a fifth of them returned to their homes. By October 1995, Serbian Krajina has been cleared of the population - there were 5 (!!!) thousand inhabitants.

The rest was a matter of technology. The reaction of the international community was restrained, but rather pro-Croat. Eastern Slavonia, the last enclave of the former Krajina, was reintegrated into Croatia without war a few years later.

Virtually the entire political and military leadership of the Serbian Krajina was subsequently convicted in The Hague. The moderate Hadžić (released after 4 years due to serious illness and died), the "radical" Babić (died in prison, allegedly by suicide) and, as is well known, Slobodan Milošević went to the tribunal. Jovan Rašković escaped trial only because he died of a heart attack in 1992. The Croats got away with a few officers. Virtually all those responsible for killing Serbs remained at large and were terribly proud and proud of their part in the ethnic cleansing.

In fact, the fall of Serbian Krajina came at a time when the Serbs, having pulled off a series of bloody, hard but clear victories, agreed to hand over their security to the international community. Milosevic had hoped to negotiate with Croatia and the West, and predictably was first used and then became a defendant himself.

The history of the Serbian Krajina offers a lesson to our country. Concessions are not perceived by the enemy as a reason to start a dialogue. Anything that we might call a "goodwill gesture" is actually perceived as a sign of weakness. Intrigue and backstabbing are all good until one moment. -- The moment when they come to kill you.

(Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator) (free version)

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Source: Объясняет Readovka. IMG: © N/A. AWIP: http://www.a-w-i-p.com/index.php/aM02