Breaking the law

America has a cop problem.

Black people everywhere have a cop problem.

Humanity has a cop problem. More than ever.

In the last few days, cops in Cleveland murdered the 12-year-old black child Tamir Rice for playing with a BB gun in a public park. A grand jury in Missouri failed to indict the cop that murdered the 18-year-old black teen Michael Brown as he held his hands above his head and shouted Don’t shoot. A grand jury in New York failed to indict the cop that murdered (on tape) the 43-year-old black man Eric Garner as he repeatedly gasped I can’t breathe.

There’s a lot to be said about all this, but I’m not the one to say it. There are plenty of essays by black writers and activists that expose these travesties with far more anger and elegance than I ever could; among the most powerful are The Parable of the Unjust Judge or: Fear of a Nigger Nation by Ezekiel Kweku and Not another death: Black Lives Matter by Wail Qasim. What I want to talk about is something very specific: the process and the meaning of the failure to indict the murderers of Michael Brown and Eric Garner.

Under the grand jury system a failure to indict isn’t the same as a court finding a defendant innocent; by failing to indict the two grand juries have found these killer cops to be so utterly and impeccably innocent that there can be no actual trial on any charge. Something is seriously wrong here. Grand juries usually function as a rubber stamp for the prosecution; it’s hard to imagine a grand jury throwing out a case against someone accused of plotting an act of terrorism, for instance, however spurious the evidence. These cops appear to have broken the law and got away with it. Faced with this travesty, a few familiar slogans are being thrown around: even if you don’t agree with the outcome you have to respect the decision; justice is a process, not a result; we live under the rule of law. It’s time to clear out this bullshit. Despite appearances, the law is not broken when white cops kill black people; it’s strengthened. The law is a fetish, a piece of hocus pocus magic, a ceremonial mask for power, a primitive superstition for white folk. The law is a transcendental secret, the centre of a mystery cult. It’s not a normative ideal to which actual events must conform themselves: all signifiers refer only to other signifiers – and never more so than in the case of the law, in which most pieces of legislation primarily refer to and amend other pieces of legislation. Instead the law is the hidden core of an institution of differences; more than anything, it’s an object of veneration.

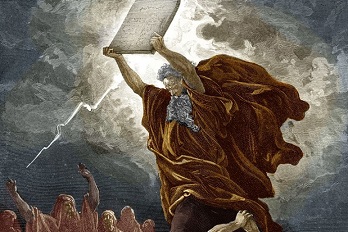

The founding scene of legality is pretty familiar. Moses climbs up a Mount Sinai wreathed in fire and lightning to receive the gift of the law as a divine inscription on tablets of stone. As he descends, he sees that the Children of Israel have abandoned their faith and melted their earrings into a golden calf for them to worship: in his fury he breaks the tablets, and only when the idol is destroyed and three thousand of the Israelites have been killed can he return to the mountain and bring back the law. It’s a myth that conforms to the Benjaminian theory of law-founding violence: before the law can begin to function, the sons of Levi must first, by virtue of might, slay every man his brother, and every man his companion, and every man his neighbour. There’s something else too: what’s objectionable about the golden calf is that it is a graven idol, a representation of a tangible thing. The true object of worship (see how even now the Torah is kissed and venerated) must be what Deleuze calls the paranoid, despotic, signifying regime of signs; an abstract and unknowable code for an abstract and unknowable God.

Given that it’s an idol, what the law says is of little importance when compared to what the law does. After smashing the tablets Moses divided the Children of Israel into those on the side of the Lord and those with the golden calf; the former to be saved, the latter to be slain. The law institutes an othering system based on a principle of proximity, in which this proximity to the law becomes an ontological attribute. Michael Brown was a criminal, a thug, a menace, because he allegedly shoplifted some cigars – because he was black, because he was distant from the law. Eric Garner was a criminal, a thug, a menace, because he allegedly sold some roll-up cigarettes – because he was black, because he was distant from the law. Without a modern-day Moses to draw the lines of distance and demarcation, this role has fallen to the police. The role of the cops isn’t to enforce or uphold the law, but to set the order for its worship. Something is legal because a cop does it, or illegal because a cop forbids it. Cop action constitutes legality. The law is a function of the cops, and cops are a function of privilege.

The word privilege comes from the Latin for private law, but (as dramatised by Kafka) the law is always a secret and always private: privilege is the law, and the law is privilege. More accurately: white supremacy is the law, and the law is white supremacy. The founding documents of the United States, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, to which all US laws refer, spoke of the inalienable right of all to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness while millions of black people were enslaved. This isn’t a contradiction, or at least not a meaningful one; the thetic content of law is irrelevant. What these texts did was to form a political subject, one which had life, liberty, and happiness, one that was landed, male, and white, one that would be protected by the holy magic of legality.

Why won’t grand juries indict cops that break the law? Because it’s impossible for a cop to break the law. White people – those close to the law – are taught from an early age to see cops as living embodiments of legality, and in a way this is true. (Black people are taught from an early age to see cops as an imminent danger to life, and this is true in every way.) The law can’t break itself; by letting killer cops go free, jurors are just acknowledging its catechism. But the law can still be broken: Moses broke it once, shattering the tablets of stone on his way down from Sinai. It can be done again. Breaking the law means eradicating its system of distances and divisions: overturning capitalism and demolishing white supremacy, so that no more innocent people will have to die.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Image: Moses zerbricht die Gesetzestafeln (Exodus 32, 19-20), gezeichnet von Gustave Doré

Source: Idiot Joy Showland. URL: http://www.a-w-i-p.com/index.php/2014/12/04/breaking-the-law